Coding for Conversations

- Masterplanning / Urban Design Written by Mark BlainThe first phase of National Model Design Code (NMDC) pilot projects recently came to a close, with a second phase due to start this Autumn.

At OPEN we have been proud to work on Sefton Council’s pioneering first phase coding pilot, teaming with Hyas and BE Group to create an area design code for a mixed-use, canal-side corridor which aims to support the wider regeneration of an inner urban neighbourhood.

Revised NPPF and NMDC have placed renewed focus on design guides and codes, promoting them as frameworks for ‘beautiful and distinctive places’.

The first phase pilots have reaffirmed this potential, but have also reminded us that the value of such frameworks often lies more in the process than the documented output itself.

Working on one of the coding pilots, and seeing the progress of others, has renewed our belief in coding as a route to positive, cross-disciplinary working, and a means of demystifying – or decoding - what good design means for a particular place.

Roundtable discussions with other teams have been refreshing, showcasing the benefits of well-considered, well-produced design codes. It is clear that they can be positive collaboration tools that facilitate conversation, with content shaped to the specific issues of a particular location or community, and tailored to a Local Authority’s strategic objectives, approach to implementation and available resources.

Key Takeaways

Our work has helped to highlight some key ingredients to be integrated into any coding process.

1. Aim to enable, rather than control

Despite varied contexts and objectives, the first phase pilots seemed to find common ground over the need for an ‘enabling’ approach over a ‘controlling’ approach.

This means moving away from the idea of a design code being a regulator or enforcer of rules, towards being a tool to facilitate dialogue; between all parties involved in the design, implementation and end use of buildings and spaces.

Our work at Sefton aimed to help officers, landowners, developers and local communities to talk about the design of existing and potential future places, and understand what ‘good’ design might mean in the context of a specific inner urban neighbourhood.

This was done without the need to set a regulatory plan, or even a masterplan in the traditional sense. Instead, the code has been able to define ambitions, key principles, concepts and parameters in a way that invites two-way conversations. The code does not shy away from the need to set boundaries, but it also invites interpretation. It aims to enable informed, well-balanced development proposals and decisions.

2. Build partnerships for long term application

In the past, some design code have been criticised for being complicated technical documents produced by a select few ‘design experts’. Sometimes coding has been approached as something that is done to a place, rather than something that could be done by a community. This is something that NMDC aims to tackle.

Codes can sometime appear exclusive and aloof; expecting someone, somewhere to apply its requirements, somehow. This is risky and short-sighted, not only giving a code a sense of mystery (or even mistrust) amongst local communities, landowners and developers, but making it difficult for officers and members to understand, take ownership and justify compliance over the long term. This is where coding can, when done badly, risk frustrating good design rather than facilitating it.

The pilots have shown the value of approaching the coding process differently. In Sefton, we aimed to open up code production in a way that allowed local communities and stakeholders to engage with the topic of design, and explore the challenges of delivering new development against wider opportunities and constraints relating to sustainable, responsive growth.

We used the coding process to focus on common goals rooted in the character and needs of the place, showing the role that design can play in meeting expectations and aspirations, but ultimately making a positive contribution to wider, holistic and deliverable regeneration.

The aim has been to provide a platform for partnership working and consensus-building as site-specific proposals are developed further and taken through the planning process. It gives a head start when it comes to defining what kinds of development would be welcome where, and encourages people to work together to find deliverable solutions.

3. Accessible themes and content

NMDC and NPPF are clear in their aim to make design codes and guides more commonplace. To achieve this, codes must be understandable by more than a handful of industry experts, or those directly involved in the process of writing them.

Our work in Sefton has aimed to show that codes can be universally accessible and ‘approachable’ design tools, for example;

- Design principles and concepts linked to analysis and consultation outcomes: a clear premise or rationale that can be universally understood.

- Structuring outputs in a clear and legible format: keeping the document concise and practical – a manual for everyday use.

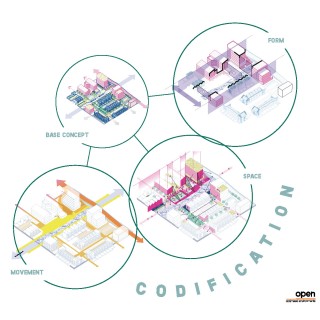

- Creating highly visual material: communicating immediately recognisable design ideas, easy to digest and translate.

The aim has been to demystify the process, focussing on the simple message that design in the built environment is ultimately about enhancing the human experience of being in and moving around places: an objective and language we can all understand.

4. Strategy over detail

Different codes will set out to tackle different scales and levels of complexity, depending on local circumstances and objectives. But, one constant coming through the first phase codes has been the importance of avoiding too much prescription of too much detail, regardless of scale and context.

At Sefton, our code covers a local area rather than one specific site. This led to early consensus that the focus should be on defining the underpinning strategic principles that will make this area come together as a coherent place, rather than the precise detail of what that must look like.

These strategic principles became the ‘musts’ of the code: the elements that developers and landowners will be expected to deliver.

It followed that the code could then give more flexibility to the way in which those more strategic level principles can be applied in detail. To do this, the code presented design concepts and illustrative detail that should … or could … be applied, offering these more as a basis for conversation (as opposed to regulation).

Conclusions

We have seen through our own work, and that of the other first phase pilots, how design coding seems to be evolving progressively, with NMDC providing helpful guidance and positive cues.

To us, this could be neatly summed up as a shift in the definition of the word ‘code’: moving away from the idea that code means a ‘set of rules’ towards the idea that code means ‘language’. That is, a design language that helps us all to understand and ‘decode’ what good design means in the context of a given geography and community.

This shift is helping design codes to be applied with more flexibility. The first phase pilots have confirmed that there is potential for broad and diverse application, revealing opportunities to move away from site-based regulatory documents towards a more liberal and strategic place-based approach.The size or complexity of a geographic area is not a barrier to establishing a common design language.

Coding too is becoming more about bringing local communities and a broad range of stakeholders into the design conversation, helping to establish locally-based frameworks that give confidence to all parties involved in implementing them, especially officers and local members who need to justify and encourage their application.

Whether it’s a site, a neighbourhood, a regeneration area, a town or a borough, coding creates constructive conversations.